-

We need an Agent OS

The opinions expressed in this article are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of my clients or employer.

Every wave of technology arrives with a grand promise. For AI agents, that promise is simple: they will take work off our hands. These intelligent systems—designed to reason, plan, and act autonomously across applications—are supposed to finally bridge the gap between information and action. The demo videos are mesmerizing. We see agents booking travel, generating reports, and handling entire workflows end-to-end. But in the real world, agents are far better at helping us do the thing than doing the thing themselves.

This is not simply a question of model capability or technical maturity. It is rooted in human psychology. Throughout history, humans have embraced tools that amplify our abilities, but we hesitate to adopt tools that remove our presence entirely. The spreadsheet did not replace the analyst; it made the analyst faster. Autopilot did not eliminate the pilot; it made flights safer. Even Google Search, the ultimate productivity amplifier, leaves the final click and decision to us. AI agents are colliding with the same truth: we are comfortable with co-pilots, but we are not yet ready for captains.

The Bull and the Bear case for AI Agents

The AI community today is split between those who believe agents are on the verge of revolutionizing work and those who see them as fragile experiments.

The optimists, including researchers like Andrej Karpathy and many early enterprise adopters, imagine a near future where agents reliably orchestrate multi-step tasks, integrating across our apps and services to unlock massive productivity gains.

The skeptics, from voices like Gary Marcus to enterprise CIOs burned by early pilots, argue that most agents are brittle, overconfident, and ultimately stuck in “demo-ware” mode—fun to watch, hard to trust.

Both perspectives are correct. The bulls see where technology could go, while the bears are grounded in how organizations actually adopt and govern new capabilities. The tension between promise and practice is not about raw intelligence alone. It is about trust, reliability, and the invisible friction of human systems that are not yet designed for fully autonomous software.

What This Means for Leaders and Builders

For a business executive, the lesson is clear: staking a transformation on fragile autonomy is reckless. The path forward is to pilot agents as co-pilots embedded into existing workflows, where they can create value without assuming total control. Early wins will come not from tearing down processes but from enhancing the teams you already have.

For a technology leader, the challenge is architectural. Building a future-proof approach means resisting the temptation to anchor on a single agent vendor or framework. Interoperability and observability will matter far more than flashy demos. Emerging standards for tool integration and context sharing will shape how agents scale safely, and the organizations that anticipate these shifts will be ready when the hype cycle swings back to reality.

And for the builders—the developers crafting agents today—the priority is survival in a fragmented ecosystem. Agents that are resilient, auditable, and easy to integrate will outlast magical demos that break on first contact with messy enterprise data. Human-in-the-loop design is not a compromise; it is a feature that earns trust and keeps your agent relevant.

The Realization: Agents Need a Home

As I worked through these scenarios, one realization became inescapable: agents are not failing because they cannot think. They are failing because they have nowhere to live. They lack persistent context across tools and devices. They lack a reliable framework for orchestrating actions, recovering from errors, and escalating when things go wrong. And most critically, they lack the trust scaffolding—permissions, security, and auditability—that enterprises demand before they let any system truly act on their behalf.

Right now, each agent is an island. They run in isolated apps or experimental sandboxes, disconnected from the unified memory and control that real work requires. This is why the leap from co-pilot to captain feels so distant.

History offers a clue about how this might resolve. Every major paradigm in computing eventually required an interface and orchestration layer: PCs had Windows and macOS, smartphones had iOS and Android, and cloud had AWS and Azure. Each of these platforms provided not just functionality but a home—a trusted environment where applications could operate safely and coherently. AI agents will need the same thing.

Call it, perhaps, an Operating System for Agents. We may not name it that in the market, but functionally, that is what must exist. The companies best positioned to build it are not the niche agent startups or the AI model providers, but the giants that already own our daily surfaces and our context: Microsoft, Apple, and perhaps Google. They control the calendars, files, messages, and permissions that agents will need to function meaningfully. Whoever creates the layer where agents can live, learn, and act—while keeping humans in control—will define the next era of AI.

The Quiet Future Ahead

If this plays out as history suggests, the rise of agents will not feel like an overnight revolution. It will feel like a quiet infiltration. Agents will first live as co-pilots within our operating systems, helping us with tasks at the edges of our attention. Over time, they will orchestrate more of our digital lives, bridging apps and services in the background. And finally, the interface itself will become the true home of agents—a layer we barely notice, because humans will still remain in the loop, just as we prefer.

The agent future, then, is not about replacing us. It is about designing the world where they can live alongside us. Only when that world exists will the real revolution begin.

-

The Four Layers of AI: How Companies Are Actually Using It

Okay, so I’ve been kicking around the whole AI thing for a while now, chatting with colleagues, clients, and partners from all corners of businesses – marketing gurus, the engineering brain trust, the suits upstairs, and the data wizards. Honestly, it’s been a bit of a whirlwind. Some people are chasing those immediate, shiny AI toys, while others are gazing way off into the future, dreaming up completely different business models.

One thing’s for sure: there’s no magic AI button that works for everyone. But after all these conversations, a sort of pattern started to emerge in my head, a way to roughly categorize how AI is actually being used out there in the real world. Not the sci-fi stuff, or the deep technical nitty-gritty, but what companies are actually doing with it right now.

Now, this isn’t some definitive truth, mind you. It’s just a way I’ve found to wrap my head around things, and it feels a little closer to reality than some of the more rigid frameworks I’ve seen floating around. I’m really focusing on the applied side of things – what’s getting built and put to work, not the theoretical research or the intricate details of how those models are trained.

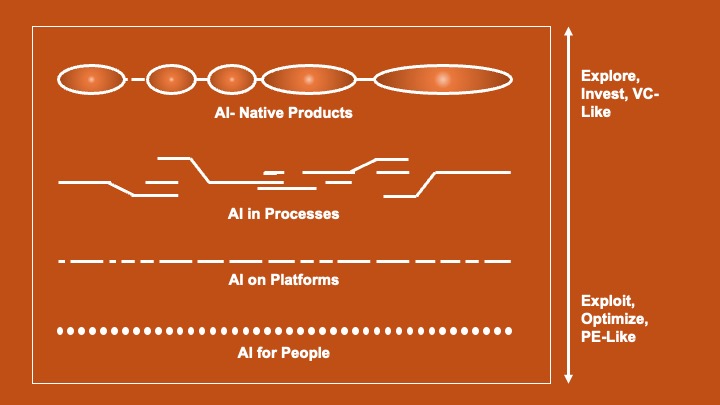

So, here’s how I’m currently thinking about it – four layers, starting with what seems like the easiest stuff and maybe moving towards the more potentially groundbreaking (though who really knows for sure, right?):

1. AI for People:

This feels like the most accessible entry point. Think about those tools that slot right into how we already work. Copilot helping you not sound like a total mess in emails or summarizing those endless meeting transcripts, or ChatGPT / Claude / Gemini (most of the times) actually answering your questions. The cool thing here is you don’t have to rip up your existing systems or change your whole workflow. You’re just giving your team some potentially smarter tools. Seems like a relatively low-stakes way to dip your toes in and maybe see some quicker wins.

2. AI on Platforms:

This is where AI starts to get baked into the software we’re already using day-to-day. Think about your CRM like Salesforce or HubSpot suddenly being a bit more insightful – maybe it’s prioritizing leads in a smarter way, suggesting your next best action, or spotting trends in your data you might have missed. A lot of this isn’t stuff you’re building from scratch; it’s coming from the vendors of these platforms. Still, it can quietly have a pretty significant impact on how things get done.

3. AI in Processes:

Now we’re starting to get into territory where companies are looking at their core operations and thinking about how AI could fit in. Automating some of those repetitive steps, making decisions a little faster, maybe even improving accuracy in certain areas. This usually means rolling up your sleeves a bit more – probably some custom development, definitely needing to tap into your own company data, and really thinking through how these changes will affect people and processes. The potential upside feels bigger here, but so does the effort involved.

4. AI-Native Products:

This feels like the wild frontier, the stuff that maybe wouldn’t even exist without AI at its core. Think about products that can generate content from scratch, make predictions that feel almost uncanny, or learn and adapt based on how people actually use them. These aren’t just souped-up versions of old products; they’re potentially completely new kinds of experiences. Definitely feels riskier to build and launch, but maybe these are the ones that could really shake things up in the long run.

As you sort of mentally climb these layers, it feels like you’re generally shifting from:

- Looking for those quick, noticeable improvements to thinking about longer-term, more strategic plays.

- Grabbing off-the-shelf solutions to needing to build more tailored, custom approaches.

- Trying to make the existing stuff a little better to venturing into creating entirely new things.

- Relying on what we’re pretty sure works to exploring what might work, with a bit more uncertainty involved.

It’s interesting to note that most companies probably won’t march through these layers in some neat, orderly fashion, and honestly, that’s probably okay. Maybe the real value isn’t about ticking off all the boxes, but more about having a sense of where you are right now and where you might want to focus your energy next.

If you’re in the thick of trying to figure out what AI means for your company, maybe this rough breakdown can be a helpful way to cut through some of the hype and make a little more sense of it all. At least, that’s what I’m hoping.

-

How AI will embed into enterprises

As enterprises try to experiment, build, and scale for/with AI (including and especially with Gen AI), there are four clear areas where the impact is going to be:

- People: While is it universally accepted that your workforce will “on average” become smarter using technology”, at the same time, two other things can be true as well. 1/ From an HBR article, “If one universal law regarding the adoption of new technologies existed, it would be this: People will use digital tools in ways you can’t fully anticipate or control.” And 2/ getting inspired from a famous source, Uncertainty principle, I extrapolate that “enterprises can’t determine with precision their velocity and momentum of AI adoption“. By enterprises I mean large companies with many functions or departments, and at least seven levels of hierarchy. At those levels of scale and complexity, it is hard to get precise information and metrics about AI usage, while simultaneously knowing whether it is useful or not.

How do I use this information? Think of employees as users or customers. At every stage of AI enablement, talk to them. Ask questions. Understand what they can, should, and would do. Compare expected behaviors against motivations and incentives to anticipate true behaviors.

Next up… Processes

- People: While is it universally accepted that your workforce will “on average” become smarter using technology”, at the same time, two other things can be true as well. 1/ From an HBR article, “If one universal law regarding the adoption of new technologies existed, it would be this: People will use digital tools in ways you can’t fully anticipate or control.” And 2/ getting inspired from a famous source, Uncertainty principle, I extrapolate that “enterprises can’t determine with precision their velocity and momentum of AI adoption“. By enterprises I mean large companies with many functions or departments, and at least seven levels of hierarchy. At those levels of scale and complexity, it is hard to get precise information and metrics about AI usage, while simultaneously knowing whether it is useful or not.

-

Meet tisit: Your Second Brain, Powered by Generative AI

Ever Felt Overwhelmed by Information? tisit Organizes Your Knowledge and Suggests What You Might Want to Know Next

Hello, dear readers!

In today’s digital age, information is abundant, but organizing it meaningfully is a challenge. How many times have you encountered a fascinating fact or pondered a question, only to lose track of it later? This dilemma is precisely what tisit aims to solve.

What is tisit?

tisit—short for “what is it?”—is not just another tool; it’s your personal learning machine. Think of it as a treasure chest for your thoughts, questions, and ideas that not only stores them but actively helps you make sense of them.

The Problem We All Face

We often come across exciting ideas or questions that tickle our curiosity. But storing and revisiting this information in a way that adds value to our lives is not easy. Traditional methods like bookmarking or note-taking don’t capture the dynamic nature of learning.

How tisit Provides a Solution

Here’s where tisit’s true power comes into play. It uses state-of-the-art artificial intelligence to not only capture your questions and curiosities but to provide well-rounded answers to them. tisit organizes this information neatly, serving as your “second brain” where you can save, nurture, and revisit your intellectual pursuits.

Taking it a Step Further: Intelligent Recommendations

But tisit doesn’t stop there. What sets it apart is its ability to make intelligent connections between what you already know and what you might find interesting. It offers recommendations that help you dive deeper into subjects you love, and even suggests new areas that could broaden your horizons. Imagine a system that evolves with you, continuously enriching your knowledge base.

Want to be Part of Something Big?

As we put the final touches on tisit, we’re looking for alpha and beta testers to help us make it the best it can be. If you’re passionate about learning and personal growth, we invite you to be a part of this transformative experience.

Stay Tuned

For more updates on tisit and how you can be involved in its exciting journey, subscribe to this blog. We promise to keep you informed every step of the way.

-

No skill left behind

Jeff Bezos is famous for Amazon’s focus on things that aren’t going to change in the next 10 years.

“I very frequently get the question: ‘What’s going to change in the next 10 years?’ And that is a very interesting question; it’s a very common one. I almost never get the question: ‘What’s not going to change in the next 10 years?’

And I submit to you that that second question is actually the more important of the two — because you can build a business strategy around the things that are stable in time … In our retail business, we know that customers want low prices, and I know that’s going to be true 10 years from now. They want fast delivery; they want vast selection.

It’s impossible to imagine a future 10 years from now where a customer comes up and says, ‘Jeff I love Amazon; I just wish the prices were a little higher,’ [or] ‘I love Amazon; I just wish you’d deliver a little more slowly.’ Impossible. […] When you have something that you know is true, even over the long term, you can afford to put a lot of energy into it.”

From the article: https://www.ideatovalue.com/lead/nickskillicorn/2021/02/jeff-bezos-rule-what-will-not-change/

Original video can be found here: https://youtu.be/O4MtQGRIIuA?t=267I have been analyzing data since 2004 – basically all my professional life. I have seen the tools people use change (from Spreadsheets and calculators to reporting tools and infographics, to even more fancy BI tools and slick dashboards. At the same time, the methods we use to analyze data have changed from basic statistics (total, average, min, and max), to advanced statistics (distributions and variance), to advanced statistics, mathematics, and computer science (forecasting, predictions, and anomaly/pattern detection).

While the methods and tools to process and present that data have changed significantly over the years, there is one core skill that is increasingly becoming more important in terms of our ability to make meaning out of data.

That skill is the ability to do analysis, and the role is of a business or quantitative analyst. I know it sounds basic – almost too simple to write about. And therein lies the key reason why many enterprises fail to use data properly within their organizations. Yes, I admit that there are other roadblocks in a firm’s ability to use data – such as access to data, understanding the meaning and acceptable use of data, having the tools and methods to process the data, and finally, the ability (and time) to interpret the meaning of data. I contest that many of these challenges are symptoms of a bigger problem – the lack of a full-time role to analyze and make meaning out of data.

As we shifted to “Big Data” around 2010s, companies quickly pivoted to creating new roles to follow the trends. Hiring data scientists was a top-5 priority for almost any organization. Then came the realization that good data science requires data that is both broad in its sources, and deep in its volume. This followed the move to data lakes to bring all the data into one place. Many companies invested in large Hadoop-based infrastructures, only to find that once data is in one place, it’s almost too much to make sense of, and very expensive to maintain. Cataloging, searching, and distributing data proved to be a big IT overhead. With the advent of the cloud, suddenly there was a new way to solve the problem – migrate to the cloud, uncouple storage and processing, and save a ton on your overheads. The move to the cloud has proven moderately challenging for many customers, and frustratingly complicated for others. The skills to build, maintain, and evolve complex architecture is a full-time job that modern technology organizations should focus on 100%.

What has not changed during this time? It is still a person’s ability to ask business questions, identify the data needed to answer those questions, apply the stat/math/cs methods to process the data, and present the information in a consumable manner. That’s the job of a data analyst, and I argue we need more of them – that is a skill that does not scale non-linearly. At least, not yet.

-

The simplest data model you can create

A person can spend years, and make a career out of designing and building Data Models. There are generic data models, industry-specific ones, and then there are functional data models. Each with its own sets of signs and symbols, sometimes its own language, and certainly, its own learning curve.

Here is an example from IBM, ServiceNow, and Teradata. SaaS companies publish their data model blueprints so that enterprises can map their internal systems to a “standard”, which makes migration/integration easy. Industry-focused institutions (such as TM Forum) publish their version to focus on industry-specific nuances and use a bunch of jargon. And finally, there are ontologies.

The simplest way to understand data model vs. ontologies is to think specific vs. generic. Data models are often application-specific (industry or software applications; hence TM Forum and SaaS providers publish their data models). IMO, Ontologies are meant to help understand what exists and how it is related, without drilling into every specific detail (although many have gone that route too). They allow for a scalable understanding of a concept, without explaining the concept in detail.

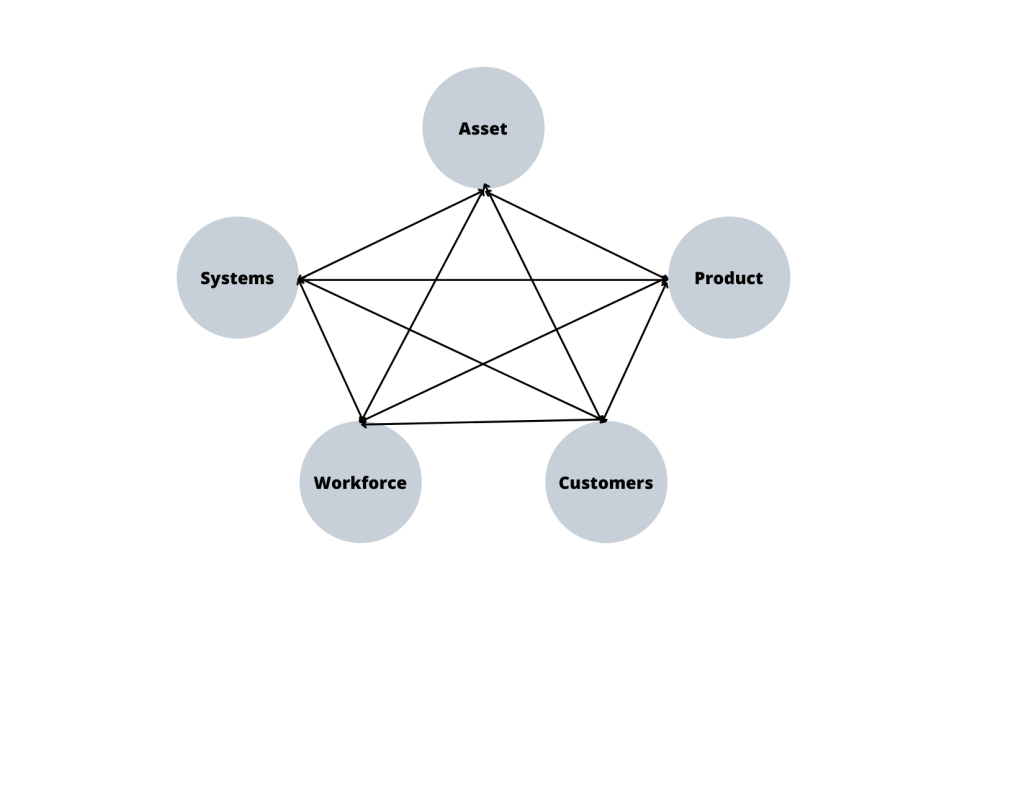

Here, I attempt to represent the simplest data model one can draw for an enterprise. It probably applies to 80% of situations and to B2B, B2C, B2B2C, or D2C business models.

Minimalist Enterprise Data Model I think that any enterprise process can be represented as a combination of one of the more basic entities (asset, product, customer, workforce, and systems). Take customer service for example. A customer tries to pay their bill online (customer -> systems). The transaction fails. The customer then calls into a contact center, talks to an employee, complains about the issue, and eventually resolves the issue. (customer -> workforce -> system).

How would this picture work for a multi-sided platform company (because everyone is a platform company, just like everyone was a technology company). In a multi-sided platform, your producers/suppliers are your consumers too. Unless you treat them like customers, serve them as customers, and retain them as customers, you won’t have a thing to sell on your platform.

Now the trick is to expand this picture as needed. But let us save that for another post.

-

The essence of Artificial Intelligence is time travel

One of my favorite writers is Matt Levin. He writes for Bloomberg, and has this natural (and funny) ability to explain complex financial concepts to lay-people like me. Check out his (mostly) daily emails and various podcast appearances (here and here) where he explains is writing process. Matt, very famously, exclaimed(?) in his blog post:

The essence of finance is time travel. Saving is about moving resources from the present into the future; financing is about moving resources from the future back into the present. Stock prices reflect cash flows into an infinite future; a long-term interest rate contains within it predictions about a whole series of future short-term interest rates.

The essence of AI (and any data-driven insight or decision) is time travel.

In a sense we time travel when we use data to understand what happened (describe), to explain why it happened (diagnose), to predict what will happen (predict), and to plan against that prediction (prescribe).

The size of data does not matter – it could be very small samples (i.e. from personal experiences) or “Big” data (i.e. a million user click-throughs). As long as we used the data that exists, to inform our knowledge, we’re doing time travel. Isn’t that exciting?

When presenting last quarters sales figures, we often describe the circumstances and results, as if they were unfolding in that very instance. Similarly, when we predict a sales forecast (using a simple regression technique, or an advanced neural net model, we’re using historical data and projecting it out in the future (with some assumptions that are expected to remain valid in the future).

So just to recap 2021, it was a breakthrough year for Tesla and for electric vehicles in general. And while we battled, and everyone did, with supply chain challenges through the year, we managed to grow our volumes by nearly 90% last year. This level of growth didn’t happen by coincidence. It was a result of ingenuity and hard work across multiple teams throughout the company. Additionally, we reached the highest operating margin in the industry in the last widely reported quarter at over 14% GAAP operating margin. Lastly, thanks to $5.5 billion of [Inaudible] small finger by now — $5.5 billion of GAAP net income in 2021, our accumulated profitability since the inception of the company became positive, which I think makes us a real company at this point. This is a critical milestone for the company.

Elon Musk — Tesla CEO from Q4’21 Earnings Call TranscriptAs it would be true with time travel, we must remember that moving back and forth in time is not only a little difficult, but we must accommodate for external situations (macro variables) which may have not been captured in the data. See, in the AI modeling world, we like to emphasize on data cleanliness, completeness, and consistency. A model in a computer is much cleaner and simple than the real world because our focus is on building a highly accurate model. But in that endeavor we often lose the details which we believe, at the time, to be less useful. Such as anomalous (very high or low values which seem to skew our results or exaggerate certain results) or missing values. It is very convenient to filter out rows and columns than to dive into another rabbit hole (of why the data is missing… what might have happened to the data – which is another time travel dimension).

In fact, this may be the reason why most data scientists spend less time doing EDA, or exploratory data analysis, than they should. Everyone’s looking for what the model says, so let’s give them an answer… how we arrived at the answer is a conversation for later (which we often don’t get to… until it’s too late).

-

Hello World!

Welcome to my blog about all things data. This blog is really meant to be a place where I think clearly about the topic, by writing about it.

If you happen to visit this blog, appreciate any feedback, questions, or inputs you have on the topic.

Some things to make clear before I start writing:

- About the blog title: I’m shamelessly inspired from one of my absolute favorite books/writer The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel. So I apologize in advance if it hurts his or others’ feelings (that I did that). Like the book (and the original blog), it is less about sharing new insights or silver bullets. To me, this blog is more about sharing what has not changed, and remains relevant to people who want to use data in decision making.

- About the content: I’ll mostly be synthesizing opinions and experiences from my career, as well as books/blogs/content from others who know and have done better. It’s about connecting the dots as I see it.

- About the format: it will be mostly open ended, long form, and without a specific flow. I’ll write about data-related topics as they develop in my mind, but this is not a book with a sequence of chapters to read from.

See you next time!

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.